This text was initially featured on Hakai Magazine, a web-based publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Learn extra tales like this at hakaimagazine.com.

Within the fall of 1385, in accordance with a Seventeenth-century Icelandic textual content, a person named Ólafur went fishing off the northwestern coast of Iceland. Within the chilly seas cradled by the area’s labyrinthine fjords, Ólafur reportedly got here throughout an animal that might have dwarfed his open picket boat—a blue whale, the most important animal on file, recognized within the Icelandic language as steypireyður.

Jón Guðmundsson, or Jón the Discovered, the poet and scholar who recorded Ólafur’s story, referred to as blue whales the “greatest and holiest of all whales.” For sailors who had been in peril from different, extra “evil” whales, Guðmundsson wrote, “it’s good to hunt shelter with the blue whale, whether it is shut at hand, and to remain as near it as attainable.” He went on to clarify that blue whales had been usually calm animals whose measurement alone intimidated extra harmful sea creatures.

Blue whales weren’t simply mythic protectors of medieval Icelanders, although—growing proof means that they had been additionally an vital meals supply. When the large whale surfaced subsequent to Ólafur’s boat, the person thrust his selfmade spear into the flesh of the whale. The spear would have been marked with Ólafur’s signature emblem, and if all went nicely, Ólafur would wound the whale badly sufficient that it will wash up useless on a close-by shore. Whoever discovered it will know Ólafur had dealt the lethal blow by the markings on the spear tip, and he might stake his declare on the whale’s bounty. In an period when most Icelanders survived predominantly by elevating sheep, a blue whale—which may attain greater than 30 meters lengthy and weigh as a lot as 150 tonnes—was a caloric windfall. One animal might yield 60 tonnes of meat—the equal of three,000 lambs—and, in accordance with a Thirteenth-century Norse textual content, was reportedly “higher for consuming and smells higher than any of the opposite fishes.”

But, Ólafur wasn’t so fortunate. The whale’s physique by no means turned up on Iceland’s shores. Later, although, a gaggle of hungry vacationers some 1,500 kilometers away, in Greenland, got here throughout a lately useless, beached blue whale. The celebration was led by an Icelandic chieftain, and Guðmundsson recounts that as he and his males butchered the animal, they discovered embedded inside it an iron spearhead marked with Ólafur’s emblem. Understanding they couldn’t ship Ólafur his bounty, the lads ate the whale, staving off hunger.

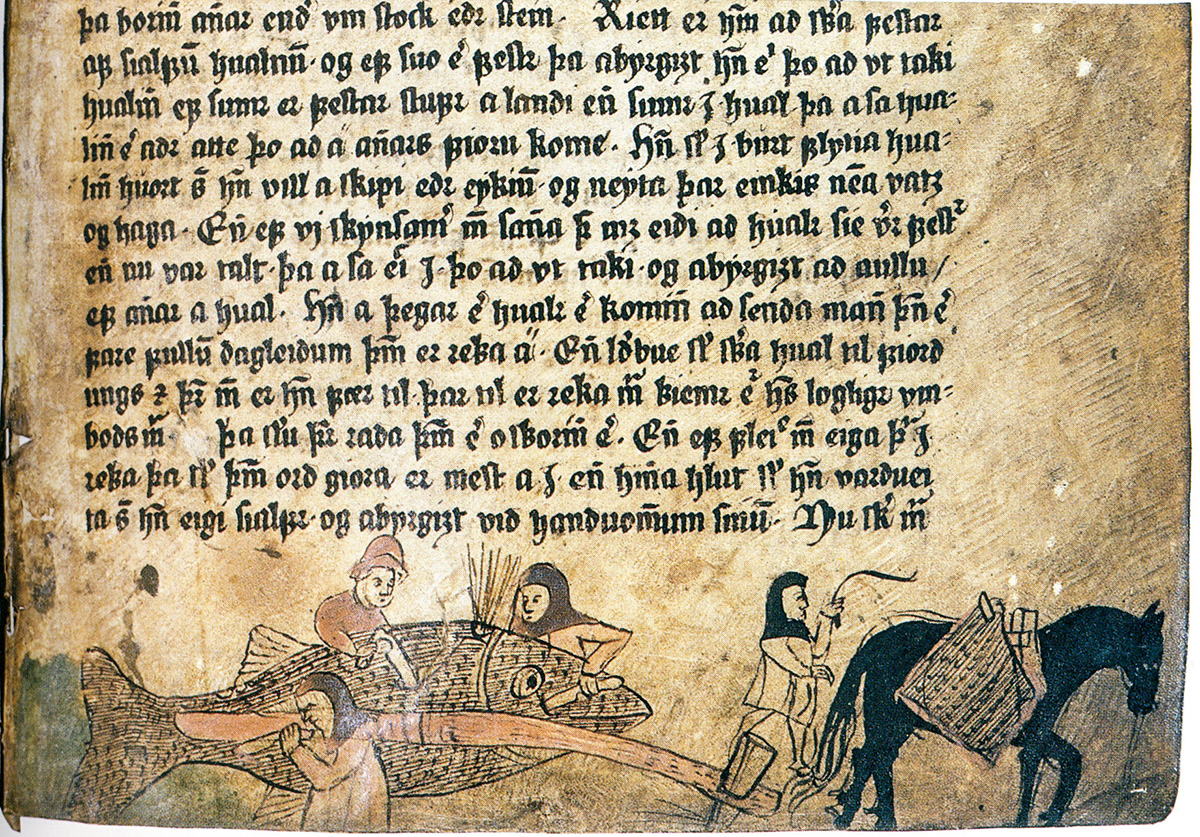

This story—one in all many related tales that environmental historian Vicki Szabo has been scouring over the past three a long time—affords a compelling glimpse into Icelanders’ interactions with blue whales. Norse texts could be scientifically correct, describing behaviors comparable to lure feeding, by which the whales open their mouths and let fish collect inside earlier than closing their jaws. However they usually mix evidence-based details with “supernatural stuff, trolls, and monsters,” says Szabo. Counting on these paperwork to color an correct image of human-whale relationships within the Center Ages, then, is difficult.

Earlier than the 2000s, the archaeological file wasn’t a lot assist both. Since Icelanders normally processed whales on the shoreline, most whalebones had been misplaced to the ocean, so their use is probably going underrepresented within the archaeological file. Zooarchaeologists didn’t establish whalebones by species; they solely categorized them as “giant whale” or “small whale.” Whales’ slippery preservation led Twentieth-century consultants to name them the “invisible useful resource.”

And although whales had been an vital supply of cultural traditions, constructing supplies, and protein in lots of northern cultures, most communities centered their looking on smaller, extra manageable species. Had been medieval Icelanders actually looking blue whales centuries earlier than the invention of exploding harpoons and quicker steam-powered ships? In that case, how had been they doing it, and the way usually? And what can these interactions reveal about each historic and fashionable whale populations?

Szabo, of Western Carolina College in the US, is now main a multidisciplinary team of archaeologists, historians, folklorists, and geneticists to attempt to reply these very questions.

Szabo first turned inquisitive about Icelanders’ historical past with whales within the early Nineteen Nineties. At first, she was restricted to finding out printed works just like the Icelandic sagas, a group of legendary tales recorded within the Thirteenth and 14th centuries. The sagas and different texts—together with these written by Jón Guðmundsson—are a trove of whale tales. “These individuals talked about whales on a regular basis,” Szabo says. Typically, they particularly talked about blue whales.

By means of her early analysis, Szabo discovered that by the Thirteenth century, Icelanders had been so depending on whales that they wrote difficult legal guidelines to determine how washed-up whales had been divvied up. A whale’s measurement, the way it died, and who owned the property the place it beached all decided who received a share of the whale meat. Portioning additionally relied on who secured it to the shore; if an Icelander noticed a useless whale floating within the sea, they had been legally obligated to discover a technique to tether it to land. And hunters not solely marked their spears with their signature emblem, additionally they registered these emblems with the federal government, enhancing the possibilities that they may declare their lawful share of any whale they speared. Along with consuming whale meat and blubber, Norse individuals used the bones as instruments, vessels, gaming pieces, furnishings, and beams for roofs and partitions.

Even with authorities laws, although, whale looking was a fraught enterprise. Spearheads had been costly, crafted by Icelandic smiths utilizing iron smelted from deposits in bogs. One fisherman within the literature grew so pissed off at shedding 5 spears in a single day that he gave up looking altogether. And scavenging whales that beached themselves or turned up useless on shore nonetheless brought about drama. At the least 5 sagas inform tales of fights breaking out over the rights to stranded blue whales.

Szabo was fascinated by such tales, and inquisitive about which whale species Icelanders relied on most. But it wasn’t till the mid-2000s, when scientists pioneered new methods to research historic bones utilizing DNA evaluation and spectroscopy, that Szabo might start to reply her query. Spectroscopy, which reveals the chemical make-up of bones by analyzing collagen proteins present in bone fragments, is cheaper and quicker than DNA evaluation. It’s confirmed efficient at figuring out many whale species, together with blues, however it may well’t distinguish between sure species, comparable to proper and bowhead whales. Scientists usually use spectroscopy as an preliminary display screen of species, then clear up any uncertainties with DNA testing.

Camilla Speller, an archaeologist at Canada’s College of British Columbia who is just not concerned within the Iceland challenge, says these applied sciences have helped change our data of previous human-whale relations, in addition to our understanding of the variety of whales that historic people hunted. “Each time we do spectroscopy on an assemblage, I feel, Oh man, I wasn’t anticipating that species to look.” When Szabo and collaborators utilized DNA and spectroscopy methods to whalebones in Iceland, the result was no completely different.

Starting in 2017, geneticist Brenna Frasier, a collaborator of Szabo’s, analyzed the DNA of 124 whalebones from a dozen archaeological websites throughout Iceland courting from round 900 CE to 1800 CE in her lab at Saint Mary’s College in Nova Scotia. Over half of the bones got here from blue whales. The remainder had been a mixture of over a dozen different species. Because the local weather shifted from the medieval heat interval, which ended within the Thirteenth century, to the colder temperatures of the little ice age, proof of many smaller whale species disappeared from the archaeological file. Blue whales, nonetheless, nonetheless dominated.

When Szabo noticed the outcomes, she was “staggered.” No different tradition is thought to have relied on blue whales so frequently. That is partially as a result of blue whales usually reside within the open ocean relatively than near shore, dive to depths of 315 meters, and have a tendency to sink after they die. Then there’s the technical problem of the whales’ imposing measurement. Frasier was concerned within the necropsy of a blue whale that washed up close to Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 2021. She says it took researchers a number of days with heavy equipment to interrupt down the animal. “I had by no means been waist-deep in whale till that occasion,” she says.

Due to the challenges of looking and harvesting blue whales, Szabo’s staff of researchers had anticipated to seek out extra proof of smaller whales like pilot whales and minke whales, which might have been simpler to drive ashore and butcher and, at this time not less than, are extra considerable. In related archaeological and historic research within the Faroe Islands, the comparatively svelte pilot whale dominated. Medieval Dutch hunters favored proper whales, which come near shore and float after they die. Different conventional whaling cultures additionally are likely to want slower or extra coastal species which are extra accessible and simpler to hunt. “I discover it shocking {that a} medieval whaler would go after a blue whale,” says Speller.

However as Szabo’s staff continues to indicate, medieval Icelanders appear to have finished simply that.

That the DNA evaluation now substantiates the eye blue whales acquired in Icelandic texts is gratifying for Szabo. It signifies that Icelanders had been scavenging and sure even looking whales way back to the ninth century—roughly the time that they first arrived on Iceland’s shores. Authors like Guðmundsson weren’t exaggerating: Icelanders had been possible encountering blues and exploiting them greater than some other species of whale.

Not too long ago, the panorama has supplied additional validation that preindustrial Icelanders frequently killed and harvested these leviathans. Whereas in Iceland in 2023, Szabo and Frasier had been inspired by a colleague to fulfill the Icelandic archaeologist Lísabet Guðmundsdóttir from the Institute of Archaeology, Iceland. In a convention room on the College of Iceland, Guðmundsdóttir—who usually research driftwood within the archaeological file—informed Frasier and Szabo of a brand new archaeological website, referred to as Hafnir, that she had been digging on the Skagi Peninsula in northwestern Iceland. As waves erode the shoreline, Guðmundsdóttir stated, historic whalebones dislodge from the sediment like free tooth, providing a brand new trove of analysis supplies; Guðmundsdóttir had discovered whalebones left by residents not less than way back to the twelfth century.

Listening to this, Frasier and Szabo shared an excited look. Whereas most bones had been nonetheless on website, Guðmundsdóttir confirmed them just a few she had collected. “We had been simply astounded by this field stuffed with among the largest bones we’d ever seen from an archaeological context,” Szabo says.

Later, Szabo visited Hafnir herself. Hafnir’s fertile bays and lengthy inexperienced grass give the looks of a spot that might be best for settlement if the climate wasn’t so usually horrible. Native farmers lately informed Guðmundsdóttir that final spring’s winds had been so robust they picked up lambs and blew them downwind. Later that summer season, Guðmundsdóttir misplaced a tent on the dig website in the identical manner. “The wind and the rain can drive you insane,” she admits.

For the researchers, the struggles are price it. “I’ve by no means seen an archaeological website with this a lot whalebone falling out,” Szabo says. There are too many whalebones for it to be random beached whales, Guðmundsdóttir provides: “[People] will need to have been looking them.” Thus far, the staff has uncovered dozens, presumably a whole lot, of whalebones that had been labored or whittled by native individuals throughout many phases of settlement. They’ve additionally discovered unprecedented intact bones, like a vertebra the diameter of a steering wheel, which are so huge Szabo thinks they will need to have come from blue whales. The researchers are actually within the technique of operating their preliminary spectroscopy assessments to substantiate that blue whales are as frequent right here as they’ve confirmed to be at different Icelandic websites.

However they should act quick: each time the archaeological staff returns, extra historical past has been misplaced to the ocean. “It’s the final likelihood to get the knowledge out earlier than it simply utterly goes,” Guðmundsdóttir says.

For Szabo’s challenge, which is about to wrap up within the fall of 2024, one query stays: how precisely had been Icelanders capable of harvest so many blue whales? Ævar Petersen, an impartial Icelandic biologist and guide for Szabo’s challenge, suspects individuals could have hunted the smaller calves of the species, which could be extra curious towards people and extra manageable as soon as useless. He additionally thinks that early settlers wouldn’t have cared what species of whale they’d discovered; they’d use no matter was available. Maybe what was most obtainable was blue whales.

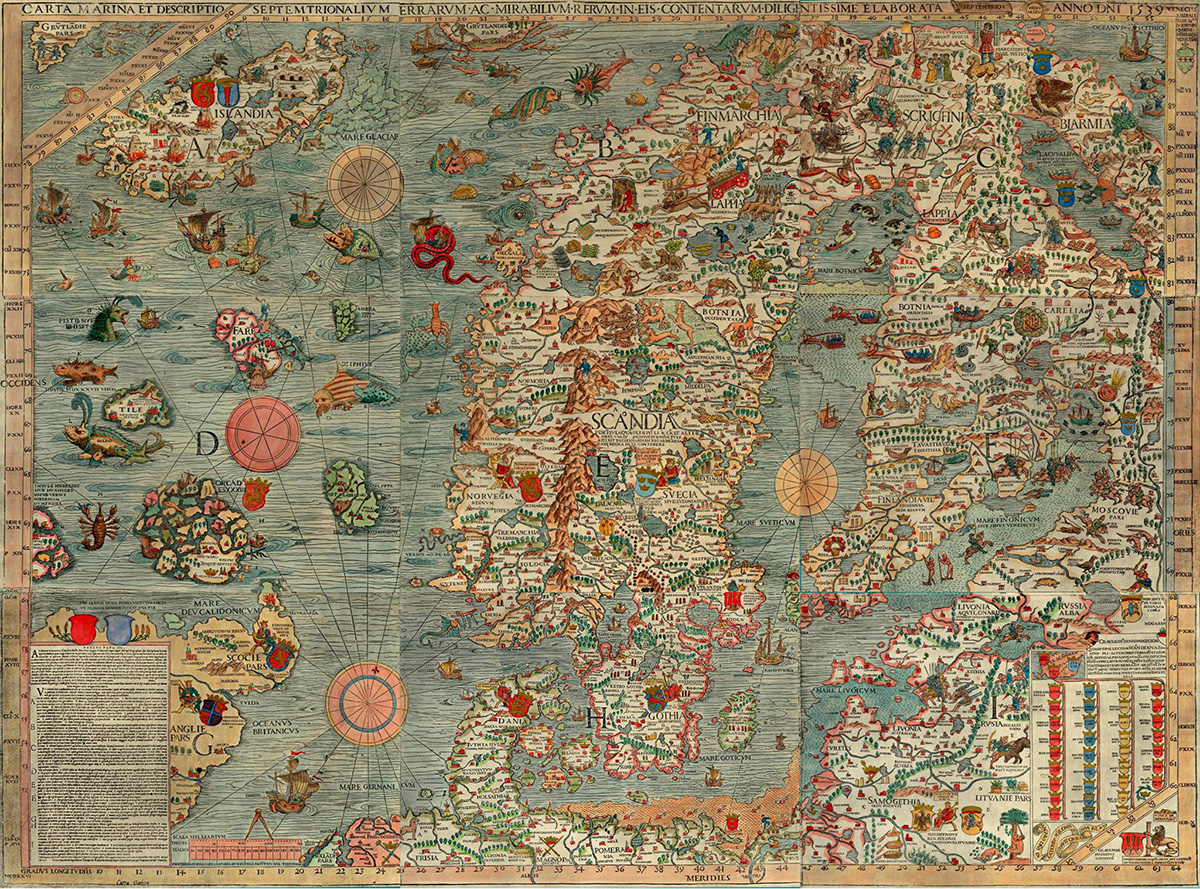

This idea is backed up by new proof that blue whales could have been extra considerable and lived nearer to shore between 900 and 1900 CE than at this time. As Petersen lately documented, for instance, 32 blue whales had been trapped in an ice-filled cove in Ánastaðir in northwestern Iceland throughout a raging Could snowstorm in 1882—an exceptionally chilly yr in Iceland when famine loomed. There have been no roads, but individuals flocked to the cove, touring over the icy panorama on foot or horseback—some from so far as 100 kilometers away—to assist kill and butcher the whales. Whale meat from Ánastaðir presumably saved a number of thousand individuals from hunger. Some meat and blubber had been eaten recent; some had been saved in particular pits referred to as hvalgrafir for so long as 4 years.

At present, discovering so many blue whales so near shore is unprecedented.

A yr after the 1882 slaughter at Ánastaðir, improved expertise allowed Norwegians to start looking blue whales at an industrial scale round Iceland. Different nations quickly adopted, and by the mid-Twentieth century, industrial whalers from the US, Japan, Russia, and elsewhere had possible massacred 90 p.c of the planet’s blue whale inhabitants. Regardless that Iceland not permits blue whale looking, industrial whaling remains to be authorized there at this time. Iceland is the one nation that permits whaling of the endangered fin whale, the second-largest whale species.

Across the identical time because the 1882 slaughter, a slight international cooling development introduced extra ice into Iceland’s coves. The mix of human pressures and an icier coast could have finally pushed blue whales offshore. Maybe, Szabo theorizes, Icelanders had been capable of harvest so many blue whales as a result of they behaved otherwise than at this time’s blue whales: industrial whaling hadn’t but decimated their inhabitants, and completely different weather conditions tempted them nearer to shores and coves. Northwestern Iceland specifically—the place Hafnir, Ánastaðir, and a number of other different archaeological websites are positioned—more and more stands out as a historic hotspot of blue whale exercise.

Northwestern Iceland can be the place Ólafur, the 14th-century hunter, speared blue whales from his open picket boat. Later in his life, Ólafur noticed a feminine whale coming into the bay close to his dwelling. In accordance with Guðmundsson’s telling, Ólafur took goal however solely punctured the animal’s dorsal fin. The scarred blue whale returned to the identical bay for 15 years afterward. Ólafur seems to have developed a private kinship with the whale, selecting to not attempt to kill her once more. However he had no downside capturing the whale’s calf. One summer season, when he raised his spear and took goal on the calf, his spear went askew, hitting the mom as a substitute.

With that, he’d had sufficient. That was the final time Ólafur speared a whale.

This text first appeared in Hakai Magazine and is republished right here with permission.