This text was initially featured on Hakai Magazine, an internet publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Learn extra tales like this at hakaimagazine.com.

In late July, dozens of brown bears congregate at Brooks Falls, in Katmai Nationwide Park and Protect on the Alaska Peninsula, to gorge on sockeye salmon catapulting their vibrant crimson our bodies upstream to achieve their spawning waters.

Enchanted, I stand with a crowd of vacationers on a picket viewing platform, observing as dominant bears rating spots on the high of the falls, and leggy subadults patrol the banks for leftover carcasses. A 350-kilogram male submerges within the frothy pool of water beneath the falls, surfacing with a salmon 10 seconds later. He clutches the fish between his two entrance paws, as if praying, then skins it entire.

I’ve at all times dreamed of touring to see the bears of Brooks Falls, a vacation spot for as much as 37,000 guests annually. However I’ve come now for a a lot smaller, lesser-known mammal—one that can take the stage when the solar units and the dusky, dying mild calls forth a groundswell of mosquitoes.

Meet Myotis lucifugus, generally known as the little brown bat. Or, as chiropterologist (bat researcher) Jesika Reimer fondly calls it, “the flying brown bear.” Little brown bats share many comparable physiological and behavioral traits with Ursus arctos. Each are slow-reproducing mammals that may dwell for a lot of a long time within the wild. Each feed in a frenzy by the summer time and autumn months to organize for a winter in torpor, a state of metabolic relaxation. But the little brown bat weighs lower than 10 grams.

“They’re so small and we’re so oblivious to them,” muses Reimer. “That’s why I really like bats a lot.”

A number of hours after observing the bears, I meet Reimer a brief distance from the falls at a log cabin that homes US Nationwide Park Service workers in Brooks Camp. She flicks on her headlamp and scans a mist web she’s erected exterior—black mesh so tremendous it’s almost invisible, strung between metallic poles that stand six meters tall. Someplace above us, as many as 300 feminine little brown bats jostle within the cabin’s heat, secure attic the place they’ve gathered for the summer time to start and rear pups—an association referred to as a maternity colony. Tonight, on the 58th parallel, with simply 4 to 5 hours of true darkness, Reimer goals to seize a number of in hopes of fixing a long-standing thriller.

Maybe as a result of bats so simply evade human consciousness, scientists know little about the place people who dwell at this far northern margin of the species’ vary spend their time by the winter months. To search out some solutions, Reimer is main the first-ever gene-flow examine of maternity colonies in Alaska exterior of the state’s extra temperate southeastern arm. How interconnected are these Myotis lucifugus populations, she wonders? And the place, precisely, are they hibernating?

We hear a fluttering from the cabin’s awning, and Reimer’s handheld acoustic monitoring system picks up a rapid-fire pulse of echolocation—high-frequency sounds that bats produce to navigate and discover meals. Not lengthy after, one snags within the web. With knowledgeable precision, Reimer gently disentangles the creature. It squints up at us, its snout squished-looking and its black ears almost as huge as its head. It’s smaller than I had imagined, simply 9 centimeters lengthy. Reimer turns the bat over in her palm and gently blows on its pale brown fur. I glimpse a pink nipple. “Lactating feminine,” Reimer says, then stretches the bat’s black wings huge on a desk. “Their wings are principally their arms,” she explains, noting that there are virtually precisely the identical variety of joints in a bat’s wing (25) as in a human hand (27). Then, she gently secures a silver ID band to the bat’s forearm and makes use of a small instrument to extract a pinprick of tissue—genetic materials for her examine—from every wing.

As she works, she invitations a number of bystanders to take a more in-depth look. “They’re really so cute,” one exclaims. One other takes a slow-motion video as Reimer releases the bat into the night time sky. She says that partaking residents in analysis is an important a part of her work to vary the dominant narrative about bats, a mammal that many individuals concern unnecessarily—and one which faces critical conservation threats.

A fungal illness referred to as white-nose syndrome is decimating bats throughout North America, killing an estimated 6.7 million because it was first detected in upstate New York in 2006. The fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, has been documented in bats in 40 US states, and its identified northern unfold consists of eight Canadian provinces. It thrives within the cool, damp situations of hibernacula, caves and hollows the place tons of to hundreds of bats huddle collectively for the winter, creeping onto their ears and noses and throughout their wings, inflicting lesions and dehydration. Contaminated bats stir out of torpor to groom themselves, spending treasured fats reserves, and sometimes starve to demise as soon as they’re depleted.

Not too long ago, in locations the place the fungus was first detected, subpopulations with genetic resilience are beginning to bounce again, however the state of affairs remains to be dire. The mortality fee of bats with white-nose syndrome can attain as excessive as 90 to one hundred pc, relying on the colony. Canada listed little brown bats as endangered in 2014 because of drastic declines in jap provinces. The USA is contemplating listing the species as well.

It’s not a query of if, however when white-nose syndrome will arrive in Alaska, doubtlessly threatening little brown bats right here, too. Reimer hopes that the gene-flow examine will put biologists one step nearer to finding the bats’ winter hibernacula. That approach, when white-nose arrives, they are going to be higher capable of monitor—and handle—the impacts.

Reimer has spent over a decade specializing in chiropterology, the examine of the species with “winged arms.” She was drawn to check bats, partly, due to the best way they’ve developed to fill ecological niches, pollinating particular flowers, distributing fruit and tree seeds that assist maintain and regenerate forests, and regulating insect populations.

Bats are extremely various of their diversifications. They’re the one mammal able to true flight, residing on each continent besides Antarctica. Subsequent to rodents, bats are the second-largest mammal group on the planet, with over 1,400 documented species and counting. These vary from huge fruits bats—the dimensions of a small human youngster—to the tiny bumblebee bat, which weighs in at simply two grams. The fish-eating bat, in the meantime, has elongated ft for raking the floor of the water to catch fish and crustaceans. And the Mexican long-tongued bat makes use of its lengthy, tubular tongue—almost half the size of its physique—to feed on nectar. Bats are the key pollinators of over 500 totally different plant species, boosting each pure habitats and human agriculture.

Regardless of these wonders, the bat has an unfair fame as a “bloodthirsty, rabies-carrying rodent,” Reimer says. “In North America, lower than two p.c of untamed bats take a look at optimistic for rabies, a quantity considerably decrease than, say, foxes,” she factors out. In 2021, solely three folks in america died from rabies contracted from bats.

And even when bats aren’t feared, they’re usually neglected. Many scientists and conservation organizations favor extra charismatic megafauna: wolves, humpback whales, and, little question, brown bears. However Reimer likes an underdog. “I’d a lot slightly go hike within the woods and take a look at issues nobody else has cared about,” she says. “I wish to ask the questions that haven’t but been requested.”

Reimer grew up in Yellowknife, within the Northwest Territories (NWT), labored as a tree planter in northern Alberta, and tromped alongside caribou trails as a analysis technician in Greenland. She fell in love with bats as an ecology main on the College of Calgary in southern Alberta, finding out the diets of bats killed by wind generators. However she at all times longed to return to the North.

Then, in 2010, cavers stumbled upon an unlimited bat hibernaculum in a cave system nestled within the boreal forest exterior Fort Smith, NWT, the place hundreds of little browns have been overwintering. Reimer had discovered her ticket residence. She spent a number of seasons there finding out bats at their maternity colonies, conducting acoustic monitoring and seize surveys. Her analysis confirmed that, on the sixtieth parallel, little brown bats exit torpor at cooler temperatures and give birth later than their counterparts within the US decrease 48—seemingly a bodily response to the northern setting. Finally, Reimer migrated west to take a analysis place with the Alaska Heart for Conservation Science on the College of Alaska Anchorage, and he or she started finding and amassing knowledge from maternity colonies in Alaska.

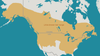

The little brown is likely one of the most generally distributed bat species in North America, present in all states, provinces, and territories besides Nunavut, the place the forests that the bats favor shrink into tundra. Although 5 different resident bat species are present in southeast Alaska, the little brown bat is the one documented species north of this area, with a identified vary extending all the best way to the sixty fourth parallel.

When Reimer moved to Alaska, she and her colleagues had solely scant information of the behaviors of little brown bats there. Some scientists weren’t even positive if mist netting can be potential. However Reimer obtained common calls from owners about bats roosting of their attics, and the primary night time she arrange a web in Anchorage, she captured dozens. It was clear they have been making a house. However how precisely does a nocturnal, hibernating species thrive in a spot the place true darkness can final lower than two hours on summer time solstice, and extra frigid winters demand heftier fats shops?

Brown bears can gorge all day and night time by the summer time and fall. However bats depend on darkness to guard them from predators whereas they forage, and so should pack on fats in brief, intense feeding spurts, says Reimer. In addition they can’t get too fats, or they gained’t be capable to fly to their hibernaculum when the time comes. Utilizing acoustic monitoring gadgets to report and analyze feeding frequencies, Reimer has begun to kind out how the bats make it work. For instance, within the Far North, they fly at nightfall—what Reimer calls “extra-solar flights”—regardless of better vulnerability to owls and different raptors.

The chilly additionally poses critical challenges for Myotis lucifugus in Alaska. Not solely can little browns get frostbite on the information of their ears, however meals is usually extra scarce. The species is insectivorous, and particular person bats can eat their weight in mosquitoes, moths, midges, and mayflies in a single night time. They’re adept at “aerial hawking”—scooping bugs into their mouths with their tails or wing membranes. When the temperature plummets, so do accessible bugs, and little browns have tailored to enter torpor as simply as flicking a swap. “If there’s a foul climate occasion, or no meals, bats can save power slightly than go discover power which doesn’t exist,” explains Reimer.

Little brown bats in Alaska have additionally developed a extra various eating regimen than southern populations. In 2017, researchers discovered that, along with catching arthropods on the wing, they “glean” them from webs and foliage, including orb-weaver spiders and others to their menu. Within the face of local weather change and shifting habitats—together with the northerly growth of the treeline—this versatility may very well be advantageous.

However there’s one factor Reimer hasn’t been capable of kind but. Since 2016, she’s positioned greater than 25 summer time maternity colonies. She has but to seek out any winter hibernacula.

Twenty kilometers southeast of Brooks Camp, I observe Reimer down a path that plunges into the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. The slopes are densely forested, a stark distinction to the valley ground, which is roofed in pink pyroclastic rock. That’s a results of the 1912 eruption of Novarupta, a magma vent on the base of close by Mount Katmai—the most important volcanic eruption within the twentieth century.

We move into an ethereal grove of birch the place there’s loads of house to maneuver between the bushes or, when you’re a bat, to fly. “Little browns love open forest canopies like this one for foraging,” Reimer says. “As soon as you recognize bat conduct, you begin to see their habitat in every single place. You’ve obtained to suppose like a bat.”

The chiropterologist is deeply interested in the place bats’ minds are main them on the panorama to hibernate, and whether or not they’re spending the winter in massive or small teams. Some migratory bats journey fairly far, Reimer notes. For instance, the European Nathusius’ pipistrelle flies over 2,000 kilometers to hibernation areas. After all of the samples she’s amassing have been analyzed, she hopes to publish the outcomes subsequent winter. Reimer wonders: Will they point out some degree of genetic isolation amongst northern Alaskan bats? Or will they present that populations are linked? If linked, that might imply the bats congregate in bigger winter colonies, maybe in a cave someplace. That may result in fast transmission of lethal white-nose syndrome, when it arrives, and add urgency to administration efforts.

However Reimer’s speculation—and her hope—is that bats right here behave in another way than their southern counterparts. There’s good purpose to suppose so, primarily based on recent findings in southeast Alaska by biologist Karen Blejwas. Beginning in 2011, Blejwas glued radio tags, weighing 0.3 grams, onto dozens of bats from summer time roosts close to Juneau, Alaska, in hopes of discovering their hibernacula. Within the late fall, she boarded a fixed-wing airplane outfitted with radio telemetry. She flew at sundown, circling the place the bats swarmed, ready for one in every of them to make a transfer so she may observe. Generally she’d get a sign solely to have it disappear. “It was like searching for a needle in a haystack,” recollects Blejwas.

Then, three years after Blejwas started her search, her analysis workforce struck gold. The primary-known Alaska hibernaculum wasn’t a cave with 1,000 bats; it was a small hole, tucked beneath rocky scree on the aspect of a steep ridge, with only a handful of occupants.

Since then, Blejwas has discovered 10 hibernacula in unassuming locations: beneath tree stumps and mossy rubble, in a jumble of rocks, tucked into upended root balls on toppled bushes. She arrange path cameras at a number of the websites and noticed bats swarming exterior and coming into their hibernacula. They have been all small colonies, ranging in dimension from one to 12 bats.

Might the identical factor be occurring round Katmai Nationwide Park and in different elements of Alaska, over 1,000 kilometers away? The distinctive hibernating technique may make little brown bats right here extra resilient towards illness, Reimer says. “In the event that they’re disconnected populations and utilizing these small cracks and crevices like biologists are seeing in southeastern Alaska, it may doubtlessly gradual or halt the unfold of white-nose syndrome,” just by limiting the variety of bats it will possibly infect without delay. Physiologically, nonetheless, little browns within the North are simply as susceptible as populations within the South. They’re a small species with out sufficient fats reserves to outlast the fungus, although one latest examine signifies that different elements, reminiscent of genetic variations in metabolic charges throughout hibernation, play a job in figuring out which people survive.

We emerge from the forest and observe the steeply reduce financial institution of the churning and tumbling Ukak River. Reimer stops and factors at one thing throughout the surging water. I’m not solely positive what she’s taking a look at. Then, I see it: a collection of cracks and crevices working by the volcanic rock wall, slight sufficient for a bat to take refuge in.

The solar units at 10 p.m. in King Salmon, a small fishing neighborhood of 300 residents on Alaska’s Bristol Bay. That is the launch level for visiting Katmai Nationwide Park, about an hour-long boat journey from Brooks Falls, and Reimer and I are again for one final survey earlier than I depart, driving by the nightfall in a Park Service truck to search for promising websites.

We pull in subsequent to a clutch of run-down outbuildings piled with fishing buoys. Reimer hops out to examine an outdated storage shed that has “all of the substances” of a spot that bats would like to roost in: it has a excessive ceiling, an attic, and sun-bleached picket shakes that bats may simply slide beneath to take refuge. However she finds only some dried guano pellets. Regardless of every part she is aware of about bat preferences, she confesses that probably the most dependable approach to find a bat roost is when a house owner calls to complain about one.

Usually, owners need colonies eliminated. Dwelling with bats isn’t straightforward. Hungry juveniles are noisy, and bat urine stinks. Over time, structural injury can happen. And residing near any wildlife can pose some actual dangers, together with the unfold of illness, although with bats that is extraordinarily uncommon. In the meantime, the advantages of getting bats round, reminiscent of their being the principle predator of disease-spreading, night-flying bugs like mosquitoes, are vital and measurable.

But, Reimer has heard tales of householders firing bear spray into their roofs or pouring bleach into their partitions; usually, they kill total colonies. Bats aren’t like mice, which might replenish their numbers shortly by having 5 to 10 litters per 12 months. And greater than 50 p.c of bat species, together with the little browns, face the risk of steep population decline or extinction over the subsequent 15 years. “When you exterminate a bat colony, that colony isn’t coming again,” says Reimer. “It might be like killing all of the bears at Brooks Falls. The next 12 months, there gained’t be any bears.”

In order Reimer works on her surveys, she additionally works on the general public, hoping to assist extra folks be taught to understand bats. She tells owners who report colonies that bats aren’t prone to chew insulation and wires like mice. She additionally makes positive they know that the bats will depart by late August. She recruits owners to take part in efforts to depend bats as they emerge for the night time—one of many methods researchers get an thought of populations—or to assist with one in every of her seize surveys. Seeing little browns up shut and studying about their distinctive adaptive biology and behaviors usually adjustments folks’s minds about them, she says: “They begin to care about ‘their’ bats.” And as soon as the bats have left for the winter, owners can seal off their houses in order that the bats discover a extra acceptable place the next 12 months.

Earlier than full darkish, Reimer will get a intestine feeling concerning the three-story Park Service house constructing the place we’ll bunk for the night time. We head again and erect mist nets, then arrange her area tools on the tailgate of the truck within the parking zone. It isn’t lengthy earlier than we hear the acquainted flutter of wings from the constructing’s awning. A shadowy type swoops down, arcs again up, dives once more, and lands softly within the web. It’s among the many final for this explicit examine—yet another unwitting helper within the effort to safe its species’ future within the Far North.

This text first appeared in Hakai Magazine and is republished right here with permission.